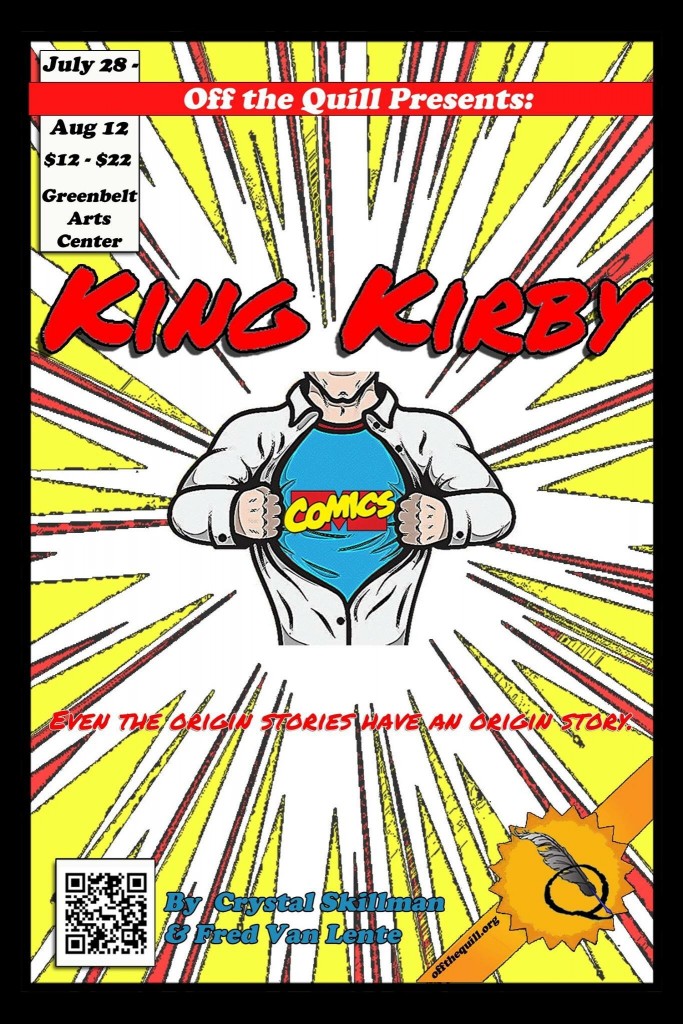

Coincidentally, a press release from Bob Batchelor came through today that ties in strongly with the play King Kirby which is currently running in Greenbelt. The paragraph where Goodman asks for more Westerns (or whatever is selling) is a recurring episode in the play, as is this characterization of Stan Lee. In his upcoming biography of Stan Lee, Batchelor writes about the creation of Marvel's first superhero character, and Jack Kirby's role in it. With his permission, here's info on his book and the excerpt (which, if you think it gives Lee too much credit, bring it up with Bob please).

Fifty-five years ago the Amazing Spider-Man debuted in a comic book series that faced cancellation for low sales. If it weren’t for a stream of fan letters and readers gobbling up the book, one of the world’s most iconic superheroes would have died an untimely death.

The story behind Spider-Man’s creation and appearance in Amazing Fantasy #15 is a tale filled with intrigue, and more importantly, Stan Lee’s calculated risk. The famed editor and writer deliberately ignored his boss – publisher Martin Goodman – who rejected the character, because “people hate spiders.” Unable to get Spider-Man out of his head, Lee had an origin story printed in AF #15. The overwhelming response and extraordinary sales would transform Marvel from a publishing also-ran to the hippest, hottest publisher on the planet.

Below is a 1,500-word excerpt on Spider-Man’s creation by noted biographer and cultural historian Bob Batchelor, which is excerpted from his new book

Stan Lee: The Man Behind Marvel (published

September 15, 2017).

Batchelor, who teaches at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, is the author of more than 25 books, including

Stan Lee: The Man Behind Marvel (Rowman & Littlefield, September 2017, adult trade, retail $22.95). Amazon:

http://amzn.to/2q4lNYe

A lifelong comic book fan and noted media resource, he has been an editorial consultant for numerous outlets and been quoted in or on BBC Radio World Service, Today.com, Columbus Dispatch,

msnbc.com, The Miami Herald, The Sydney Morning Herald, The Dallas Morning News, Taiwan News, Associated Press, The Guardian, and The Washington Post.

Spidey Saves the Day!

By Bob Batchelor

All lean muscles and tautness, a new superhero bursts from the page. Swinging right into the reader’s lap, the hero is masked, only alien-like curved eyes reveal human features, no mouth or nose is visible. His power is alarming: casually holding a ghoulish-looking criminal in one hand, while simultaneously swinging from a hair-thin cord high above the city streets. In the background, tiny figures stand on rooftops, looking on and pointing in what can only be considered outright astonishment.

The superhero is off-center, frozen in a moment, as if a panicked photographer snapped a series of frames. The image captures the speed, almost like flight, with the wind at his back. The hero’s deltoid ripples and leg muscles flex. Some mysterious webbing extends from his elbow to waist. Is this a man or creature from another world?

The answer is actually neither. Looking at the bright yellow dialogue boxes running down the left side of the page, the reader learns the shocking truth. This isn’t a grown man, older and hardened, like Batman or Superman, one an existential nightmare and the other a do-gooder alien. No, this hero is just a self-professed “timid teenager” named Peter Parker. The world, he exclaims, mocks the teen under the mask, but will “marvel” at his newfound “awesome might.”

It is August 1962. Spider-Man is born.

Spider-Man’s debut in a dying comic book called

Amazing Fantasy happened because Stan Lee took a calculated risk. He trusted his instincts. Rolling the dice on a new character meant potentially wasting precious hours writing, penciling, and inking a title that might not sell. The business side of the industry constantly clashed with the creative, forcing fast scripting and artwork to go hand-in-hand.

In more than two decades toiling as a writer and editor, Lee watched genres spring to life, and then almost as quickly, readers would turn to something else. War stories gave way to romance titles, which might then ride a wave until monster comics became popular. In an era when a small group of publishers controlled the industry, they kept close watch over each other’s products in hopes of mimicking sales of hot titles or genres.

Lee calls Marvel’s publisher Martin Goodman, “One of the great imitators of all time.” Goodman dictated what Lee wrote after ferreting out tips and leads from golf matches and long lunches with other publishers. If he heard that westerns were selling for a competitor, Goodman would visit Lee, bellowing, “Stan, come up with some Westerns.”[1]

This versatility had been Lee’s strength, swiftly writing and plotting many different titles. He often used gimmicks and wordplay, like recycling the gunslinger Rawhide Kid in 1960 and making him into an outlaw or using alliteration, as in Millie the Model.

A conservative executive, Goodman rarely wanted change, which irked Lee. The writer bristled at his boss’s belittling beliefs, explaining, “He felt comics were really only read by very, very young children or stupid adults,” which meant “he didn’t want me to use words of more than two syllables if I could help it…Don’t play up characterization, don’t have too much dialogue, just have a lot of action.” Given the precarious state of publishing companies, which frequently went belly-up, and his long history with Goodman, Lee admits, “It was a job; I had to do what he told me.”[2]

Despite being distant relatives and longtime coworkers, the publisher and editor maintained a cool relationship. From Lee’s perspective, “Martin was good at what he did and made a lot of money, but he wasn’t ambitious. He wanted things to stay the way they were.”

Riding the wave of critical success and extraordinary sales of

The Fantastic Four, Goodman gave Lee a simple directive: “Come up with some other superheroes.”[3]

The Fantastic Four, however, subtly shifted the relationship. Lee wielded greater authority. He used some of the profit to pay writers and editors more money, which then offloaded some of the pressure.

Launching Spider-Man, however, Lee did more than divert the energy of his staff. He actually defied Goodman.

For months, Lee grappled with the idea of a new superhero with realistic challenges that someone with superpowers would face living in the modern world. The new character would be “a teenager, with all the problems, hang-ups, and angst of any teenager.” Lee came up with the colorful “Spider-Man” name and envisioned a “hard-luck kid” both blessed and cursed by acquiring superhuman strength and the ability to cling to walls, just like a real-life spider.[4]

Lee recalls pitching Goodman, embellishing the story of Spider-Man’s origin by claiming that he got the idea “watching a fly on the wall while I had been typing.”[5] He laid the character out in full: teen, orphan, angst, poor, intelligent, and other traits. Lee thought Spider-Man was a no-brainer, but to his surprise, Goodman hated it and forbade him from offering it as a standalone book.[6]

The publisher had three complaints: “people hate spiders, so you can’t call a hero ‘Spider-Man’”; no teenager could be a hero “but only be a sidekick”; and a hero had to be heroic, not a pimply, unpopular kid. Irritated, Goodman asked Lee, “Didn’t [he] realize that people hate spiders?”[7] Given the litany of criticisms, Lee recalled, “Martin just wouldn’t let me do the book.”[8]

Realizing that he could not completely circumvent his boss, Lee made the executive decision to put Spider-Man on the cover of a series that had previously bombed, called

Amazing Fantasy. Readers didn’t like

AF, which featured thriller/fantasy stories by Lee and surreal art by Steve Ditko, Marvel’s go-to artist for styling the macabre, surreal, or Dali-esque. It seemed as if there were already two strikes against the teen wonder.

Despite these odds and his boss’s directive, Lee says that he couldn’t let the nerdy superhero go: “I couldn’t get Spider-Man out of my mind.”[9] He worked up a Spider-Man plot and handed it over to Marvel’s top artist, Jack Kirby. Lee figured that no one would care (or maybe even notice) a new character in the last issue of a series that would soon be discontinued.

With Spider-Man, however, Kirby missed the mark. His early sketches turned the teen bookworm into a mini-Superman with all-American good looks, like a budding astronaut or football star. Lee put Ditko on the title. His style was more suited for drawing an offbeat hero.

Ditko nailed Spider-Man, but not the cover art, forcing Lee to commission Kirby for the task, with Ditko inking. Lee could not have been happier with Ditko. He explained: “Steve did a totally brilliant job of bringing my new little arachnid hero to life.”[10] They finished the two-part story and ran it as the lead in

AF #15. Revealing both the busy, all-hands state of the company and their low expectations, Lee recalled, “Then, we more or less forgot about him.”[11] As happy as Lee and Ditko were with the collaboration and outcome, there is no way they could have imagined that they were about to spin the comic book world onto a different axis.

The fateful day sales figures finally arrived. Goodman stormed into Lee’s office, as always awash in art boards, drawings, mockups, yellow legal pads, and memos littering the desk.

Goodman beamed, “Stan, remember that Spider-Man idea of yours that I liked so much? Why don’t we turn it into a series?”[12]

If that wasn’t enough to knock Lee off-kilter, then came the real kicker: Spider-Man was not just a hit, the issue was in fact the fastest-selling comic book of the year, and maybe that decade. Lee recalls that

AF skyrocketed to number one.[13]

The new character would be the keystone of Marvel’s superhero-based lineup. More importantly, the Fantastic Four and Spider-Man transformed Marvel from a company run by imitating trends into a hot commodity. In March 1963,

The Amazing Spider-Man #1 burst onto newsstands.

Fans could not get enough of the teen hero, so Lee and Marvel pushed the limits. Spider-Man appeared in

Strange Tales Annual #2 (September 1963), a 72-page crossover between him and the Human Torch. And in

Tales to Astonish, which had moved from odd, macabre stories to superheroes, Spidey guest-starred in

#57 (July 1964), which focused on Giant-Man and Wasp. When

The Amazing Spider-Man Annual #1 appeared in 1964, with Lee dubbing himself and Ditko “the most talked about team in comics today,” it featured appearances by every Marvel hero, including Thor, Dr. Strange, Captain America, and the X-Men.

Spider-Man now stood at the center of a comic book empire. Stan Lee could not have written a better outcome, even if given the chance.

All this from a risky run in a dying comic book!

______________________________

_

[1

] Mark Lacter, “Stan Lee Marvel Comics Always Searching for a New Story,” Inc., November 2009, 96.

[2

] Don Thrasher, “Stan Lee’s Secret to Success: A Marvel-ous Imagination,” Dayton Daily News, January 21, 2006, sec. E.

[3

] Quoted in ibid.

[4

] Stan Lee and George Mair, Excelsior! The Amazing Life of Stan Lee (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2002), 126–27.

[5

] Ibid., 126.

[6

] Roy Thomas, “Stan the Man and Roy the Boy: A Conversation between Stan Lee and Roy Thomas,” in Stan Lee Conversations, ed. Jeff McLaughlin (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2007), 141.

[7

] Lee and Mair, Excelsior!, 127.

[8

] Thomas, “Stan the Man,” 141.

[9

] Lee and Mair, Excelsior!, 127.

[10

] Ibid., 128.

[11

] Ibid., 128.

[12

] Ibid., 128.

[13

] Stan Lee, Peter David, and Colleen Doran, Amazing Fantastic Incredible: A Marvelous Memoir (New York: Touchstone, 2015), n.p.

MR: I have not read this play, so what time frame in Kirby and Lee’s lives is it set? Is it set at the start of the Marvel Age?

MR: I have not read this play, so what time frame in Kirby and Lee’s lives is it set? Is it set at the start of the Marvel Age? WKC: There’s a funny scene where Stan Lee is a young kid and he’s writing the prose story in Captain America Comics (which was mandatory for cheaper postage rates), and Joe Simon says, “Who’s Stan Lee?” Lee says “That’s me, I changed my name just like Jack.” Jack says, “I changed my name to sound less Jewish ,” and Joe Simon tells Lee that his name sounds Chinese and he’s changed one minority for another.

WKC: There’s a funny scene where Stan Lee is a young kid and he’s writing the prose story in Captain America Comics (which was mandatory for cheaper postage rates), and Joe Simon says, “Who’s Stan Lee?” Lee says “That’s me, I changed my name just like Jack.” Jack says, “I changed my name to sound less Jewish ,” and Joe Simon tells Lee that his name sounds Chinese and he’s changed one minority for another. MR: Whether it was true or not in the real world, Kirby apparently always felt put upon by anybody he worked for, and that comes through in the play?

MR: Whether it was true or not in the real world, Kirby apparently always felt put upon by anybody he worked for, and that comes through in the play?