|

| Ben Towle |

transcribed by Mike Rhode from “The Graphic Novel” panel at Fall for the Book, George Mason University, October 14, 2017

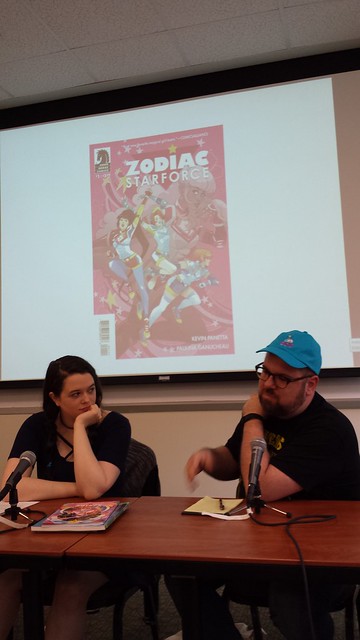

Bring the whole family for a celebration of comic books and graphic novels with artists S.L. Gallant, Paulina Ganucheau, Kevin Panetta, Jason Rodriquez, and Ben Towle. Gallant presents his artwork of a familiar hero figure as he is the longest running artist on

G.I. Joe: An American Hero. Ganucheau and Panetta co-authored

Zodiac Starforce, starring comic high school girls taking on the darkness of the earth. Rodriquez shares his graphic novel,

Colonial Comics: New England, 1750-1775, and his revolutionary idea for exciting young adults to learn about the history of colonial New England. And Towle introduces readers to the coastal town of Blood's Haven, with an ocean full oysters and even oyster pirates in his graphic novel,

Oyster War.

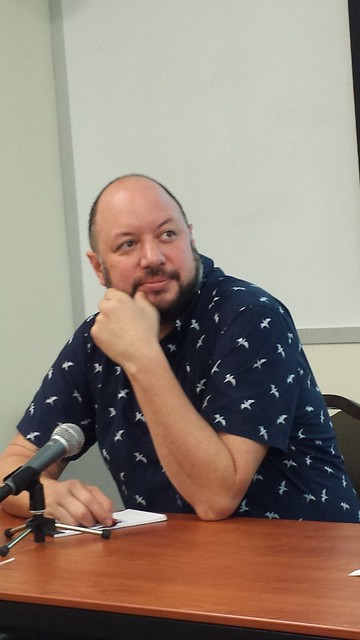

Ben Towle: We have four esteemed guest and I’m going to do a quick intro for them. They are more established in the industry than I will make it seem like, because I want to get right to some content here.

Shannon Gallant, who also goes by S.L., has penciled for all kinds of publishers like Marvel, DC, Dark Horse and Titan. He is the long-running artist on

G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero which is currently published by IDW. He is from Washington.

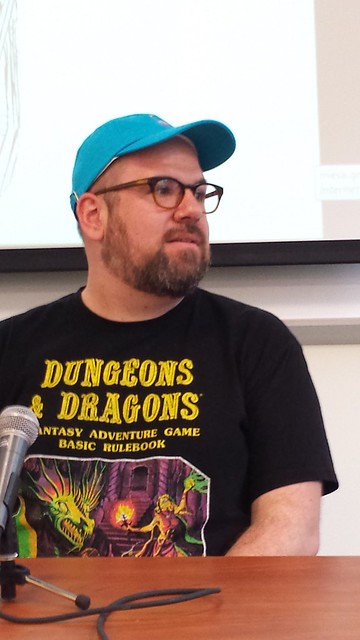

Kevin Panetta, also from Washington, is the co-creator of

Zodiac Starforce, published by Dark Horse. His first graphic novel,

Bloom, is coming out from First Second.

Paulina Ganucheau, an artist and illustrator based in Maryland, is the co-creator with Kevin of Zodiac Starforce. She has done work for DC, Marvel, Dark Horse, Random House and more.

Jason Rodriguez is a comics writer and editor who focuses on educational comics, social-justice anthologies, and historical works aimed at middle graders and young adults. He also teaches teens and adults how to make comics as a way to grasp difficult concepts.

My first question is the standard question you’ll hear at almost any comics panel, which is: How did you get into comics? With most of us, myself included, there’s usually one book or comic strip or a specific reading experience which makes a light bulb go off in your head and you say, “This is what I want to do. This is my thing.” I’ve asked these guests if they can tell us what that book or comic was for them. I’m going to start off with Shannon.

Shannon Gallant: For me, as a kid in the early seventies, my parents for Christmas would always try to buy me something to get me interested in things.

One of the things they got me were the Power Record’s comic book combos. It was a comic book that came with a 45 rpm record. My dad being in the music industry meant everyone in the house had their own turntable, as you would. I used to play it for hours and the artwork … it was Batman and I just fell in love with it. The book itself was actually drawn by Neal Adams, who at the time was the biggest name in comics. I just assumed everything in the world was supposed to look like that, because that comic book was all I ever looked at. I just fell in love with his ability with figures, backgrounds, cars, everything… it seemed like everything looked like it should look. It had a realism that just sucked me into the story and I went through that thing so many times that the 45 ended up with a skip. Years later, I found an audio file that someone had made of it, and that skip wasn’t in it, and it was driving me nuts.

I kept waiting for the skip. [audience laughs]. That was my first experience and from that point on, I was the “kid who is going to draw comic books one day. After my NFL career ends, I’m going to draw comic books.”

Ben Towle: Did you have any experience with the pre-Adams goofier Batman?

Shannon Gallant: No, this was my first exposure. The only other thing I would say was around the same time was an oversize Superfriends thing that DC published, and I fell in love with the Alex Toth section in the back. It was only like seven pages, but there was something about his artwork. Again, it was realistic figures, or naturalistic would be a better term. People didn’t have oversize muscles and women weren’t drawn exaggeratedly.

Ben Towle: Are there anything in the pages from Adams’ book that you remember finding particularly striking or is something you look back to in your own work?

Shannon Gallant: The bottom panel [of Batman’s car leaving the Batcave] was one of my favorites as a kid, because my only other experience with Batman was the tv show and I always loved how the Batmobile would come out of the cave. So, I was like, “Oh, that’s how the cave works!” I loved the car and his ability in using perspective and shadow work like in the second panel where he hides Robin’s face in total shadow. That just amazed me. I was thinking, “Oh, there’s really light.” His anatomy was always spot on and everything about it was just dramatic and caught my eye. Of course, when you’re a kid and listening to the album, the thing just practically came alive. There weren’t panel separations; it literally was a movie in my head.

The dramatic punch scene where the Joker is foreshortened – that I’ve stolen I don’t know how many times. If you look through my work, you’ll see that.

Ben Towle: Yes, but I think he stole that from Jack Kirby. We all have a habit of stealing stuff.

Kevin Panetta: Jim Aparo stole from Adams…

Shannon Gallant: It’s kind of a standard, but that’s what I see when I draw those things.

This book is practically just a blueprint for everything I draw.

Ben Towle: Let’s move on to Paulina…

Paulina Ganucheau: When I was a kid, I was into videogames before comics, which is kind of surprising because of the funnies in the Sunday papers – kids always read them, but I didn’t really care about them. I’m super into Zelda and my brother had a subscription to Nintendo Power which serialized A Link to the Past comic by the master Shotaro Ishinomori. I was around five so I was very young, but this was the moment where I thought, “This is what I want to do. “ I remember drawing my own comics, and of course they were terrible, but there was something about Ishinomori’s simplicity of line and the movement and color, how succinctly he told his story, which I was very familiar with because it was based on a game. It was very accessible to me as a young child.

You can see the vibrancy of his work, juxtaposed with the simplicity of it. You can tell he is so effective at what he does, but you know this man can hit a deadline. He has a Guinness record for the most pages ever. Something in my mind said I want to do this, and I just kept doing it.

Ben Towle: I can’t imagine where you got your color palette from.

Paulina Ganucheau: I know, right? You can see it in my work. I was super into manga, and super into anime.

Ben Towle: It did occur to me when I saw your samples that most manga we see is black and white, and you were fortunate enough to stumble upon the rare example of manga that’s full color.

Paulina Ganucheau: And this is before I was even fully obsessed with manga ,because I was about eight years old when I first discovered manga… I think it was

Sailor Moon, of course.

Zelda was a precursor to that; I didn’t even know what it was, but I already knew that I loved it and this was what I wanted to do.

Ben Towle: Kevin?

Kevin Panetta: I started reading comics when I was very young. My mom would go to the grocery store, and I wasn’t very interested in groceries, so I would hang out in the comics section and just read everything for free, like people do in Barnes & Noble now. I would read Spider-Man and X-Men and everything like that, but in my mind, those things just existed. They came fully formed out into the world, and nobody made them, and people didn’t work on them. But then I started reading

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and the creator’s names were above the title, and I became aware that Kevin Eastman writes it, and Peter Laird draws it. I thought, “Oh, that’s something I can do,” and I started following different artists. Because the Ninja Turtles comic was so weird, they had different artists who would draw everything so Jim Lawson was a little more realistic, and Mark Martin drew really cartoony things while Rick Veitch used a lot of blacks almost like a noir story. I became really aware of the different kind of stories you can tell in comics, all through

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. From there, I moved to following creators more than characters. When I was a kid I would just read Batman or Spider-man, but then I realized, “I like this writer Peter Milligan, or Neil Gaiman, so I want to see what he’s doing,” so when I was around eleven I became obsessed with different creators. And I wanted to make comics.

Ben Towle: Is that the same Mark Martin who did Runaway for Fantagraphics?

Kevin Panetta: Yes, he did

Gnat Rat and all these weird parody comics in the 80s. He did two issues of

Ninja Turtles that were really weird and he drew a parody of them called

Green-Grey Sponge-Suit Sushi Turtles, that I thought was funny when I was ten.

Ben Towle: And finally, Jason?

Jason Rodriguez: Let me preface this by saying my parents are actually here. I have two different careers in comics. When I first started, I was editing horror, thriller, historical fiction books, and eventually I got to the point when I could start doing the books I wanted to do. If it was that career, I would have shown

Groo. But I go back to these books as a kid – I was a big Charlie Brown fan as a kid. As an adult, Charlie Brown was a comic about depression, anxiety and bullying, and it was the perfect for a kid. But mainly, these hybrid comics that my parents would get for me came out once a month. They were

Charlie Brown Encyclopedias. Basically, the way it worked, they went to a grocery store, and if you bought $10 worth of groceries for $.99 you get the next volume of the encyclopedia, and if you just wanted the encyclopedia, it was $1.99. They were this fantastic merger of actual non-fiction about science, the human body, and different cultures. There were 17 volumes total and the stories were paired with sequential art in comics form. When I tried to reinvent my career to get more into educational and social justice comics, and put complex ideas across to kids, I went back to these books basically and I really tried to use them as a model. I remember as a kid, my dad worked two jobs, and my mom worked, and I needed a lot of supplemental education. Part of that was

Sesame Street and Mr. Rogers, but part of it was these Charlie Brown encyclopedias which taught me a lot outside of school when I needed more. I really tried to revisit this model. It’s kind of a cheat answer, but it’s where I am looking back right now. I remember how much influence these books had on me, and I want to try to recreate some of that for kids.

Ben Towle: I want to point out the very first Peanuts that ran. When you think about Peanuts, you think about kid’s sleeping bags with Woodstock on them , but that is pretty much the tone of a lot of the actual Peanuts comic strips.

Jason Rodgriguez: Yes, I have it tattooed on me.

Ben Towle: In comics, almost all comics-making and the process of getting your work out, comes down to problem solving. Can you each give me one example of problem solving you had to do? What the problem was and how you got around it? By problem solving, I mean everything from actual drawing problems to logistical problems of getting your books out – basically anything that involved some creative thinking. We’ll go back to Shannon – you’ve got a specific drawing problem that you want to talk about?

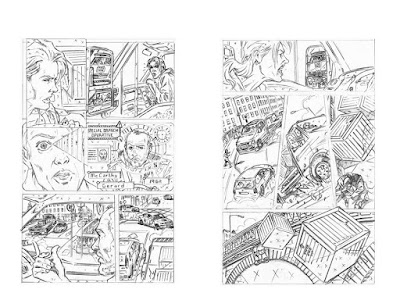

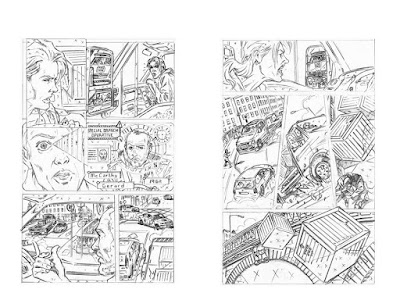

Shannon Gallant: Larry Hama, who was the writer on G.I. Joe since it started at Marvel back in the 80s when I was a kid (although it took a hiatus for years), is still writing it. Larry has a habit of trying to do things for friends and make them happy. Apparently he had a friend in Ireland, and he set a scene in Dublin. It’s a ride around the streets of Dublin. Well, I’ve never been there and I don’t know what it looks like. In the old days before the internet, you had to have a morgue file [of pictures torn out of magazine and newspapers to see how something looked when you had to draw it]. I was growing up when we didn’t have the internet so I was building a morgue file. If that was the case now, I would have been screwed because I didn’t have any pictures in the morgue file of Ireland at all, but thankfully now there’s the internet. So what I wound up doing was getting on Google Maps and ‘driving’ myself through downtown Dublin. The restaurant where the truck is crashing in and the barrels are flying everywhere is based on an actual place. These are shots of traffic from Google. I basically planned it out. Larry had this big elaborate description of what was happening, but I just had them drive around in a circle. If you follow the Google Maps, you would just see a big square in the middle of the page, but that was how I solved the problem. I tend to overdue all of my research on things like this, especially for sets and detail work. I found all these shots, and then I only used two. I got around 500 reference photos off Google Maps and I think I ended up using five or something insane.

Ben Towle: Just the traffic scene and then crashing into the restaurant?

Shannon Gallant: Yeah. But it’s one of those things that sets into your head so you get a better sense of things. Whether I show the sets or not, it at least grounds the figures for me. I try to make sure the vehicles look right, because if you go to foreign cities, the cars are designed smaller for European or Japanese cities. They’re not these big Buicks that we drive in the States and I think stuff like that is important. It always drives me nuts when I’m looking at a comic that supposed to be set in a foreign country, and I think, “The guys wouldn’t be driving a Hummer through small Italian village streets.” That’s one of the problems that I constantly faced on G.I. Joe… just where things are set. Larry loved to pick random locations like Kabul, so I ended up doing a lot of research. Thankfully for me, the internet is available now, because I don’t know that a morgue file would have been enough to deal with Larry.

Kevin Panetta: Our biggest problem was finding a format for our comic. We had a lot of problems. When we started out, we were friends and we wanted to do a comic. We had this idea called Cadets that we were going to launch as a webcomic and publish it one page at a time on the internet. And as we kept working on it, it just kept getting more complicated, and we realized, “This is a lot of work and we’re not going to get any money,” because you do webcomics for free. We decided to simplify it and there was this anime tv show that people watched inside our Cadets story, and it was called Zodiac Starforce. So we thought, “We’ll make a webcomic of that. It’ll be much simpler.” We did five pages of that, and it was a lot of work. The whole back of our graphic novel is a history of all the stuff we went through. That was not working, because when you do a webcomic and you’re doing one page at a time, you want to put a cliffhanger at the end of every page and that affects the way you tell the story.

Paulina Ganucheau: The pacing didn’t work.

Kevin Panetta: Then we decided to try to do a simple black and white minicomic…

Paulina Ganucheau: … which is also in the book if you want it.

Kevin Panetta: In that format, we were trying to simplify things, and it made things look too cute. We wanted to tell kind of a serious story. Finally, we got contacted by a publisher who asked if we could do it as a longer story – around 90 pages. And that’s when we ended up with what we have now which is putting it out through Dark Horse. We found that we could tell the story we wanted to tell and take a little more time with it because 1: we were getting paid, which helps [Paulina: That helps. Really helps] and then 2: that length gave the story a lot of room to breathe. We finally settled in and felt like we were doing the story the way we were supposed to.

Paulina Ganucheau: It was a better situation for everybody involved… and for the characters… and the story.

Kevin Panetta: Now we’ve done one of those, and we’ve just started another one and the format has worked out really well for us.

Ben Towle: One thing I noticed, as it went through various formats, the character designs changed. I remember it online, and didn’t it run in print with something having to do with a comic store here in town?

Kevin Panetta: There’s a comic store called Big Planet Comics and our very first iteration was an ad in the back of Magic Bullet newspaper. It was like Scooby-Doo and they were solving crimes and were in a band…

Paulina Ganucheau: It’s in the graphic novel too. It was one-page like Jem and Scooby-Doo meet.

Ben Towle: They were in school in this one…

Kevin Panetta: Yeah, they were in school, but the stories now are more about the character relationships so the stories are set during winter break so we don’t have to put them in class.

Ben Towle: And then there was a minicomic? I missed that one entirely.

Paulina Ganucheau: Yeah.

Ben Towle: So why did you go with a more simplified concept?

Kevin Panetta: Because it was less work.

Paulina Ganucheau: And we did it in a week.

Kevin Panetta: Before SPX – the Small Press Expo. If you’ve never been, it’s the best comics show.

Ben Towle: Absolutely, if you’re from this area and you’re not going to SPX, you’re missing out. It’s one of two or three of the best indy comics shows that you get. Independent creators, with their own books and not Marvel or DC, are hand-selling stuff, a lot of which they made themselves with silk-screening and stapling. It’s a really amazing show.

Paulina Ganucheau: It was my very first convention and it opened my eyes so much.

Kevin Panetta: Paulina didn’t draw the cover of the collection though; we got lucky enough to get

Marguerite Sauvage, a really amazing French artist. I don’t know why she drew that for us.

Paulina Ganucheau: I don’t either. We tricked her.

Ben Towle: Jason, you had some very specific issues related to historical fiction?

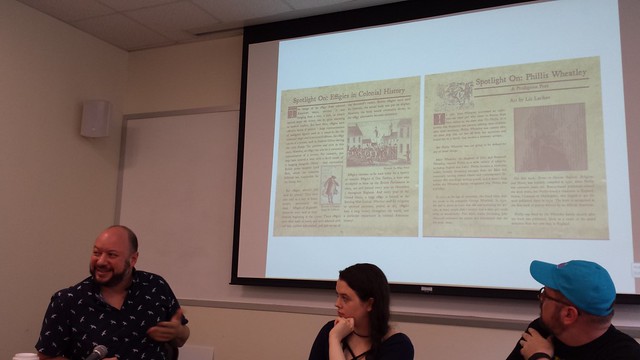

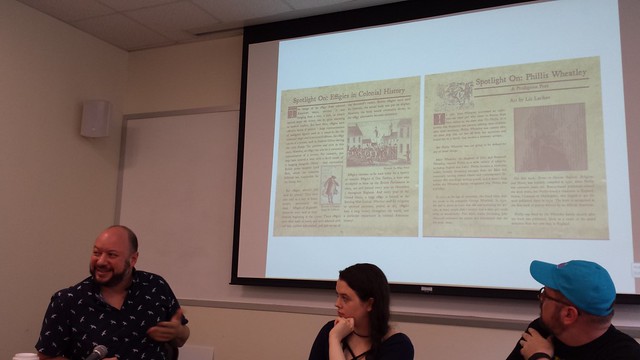

Jason Rodriguez: I’m going to focus on my colonial history books. The purpose of these books is to include under-represented narratives from colonial history. When I first sat down with my publishers, I think they were taken aback a bit by how much I wanted to put into this. I had Pulitzer Prize winners of non-fiction writing stories, professors like

Doctor Virginia DeJohn Anderson from University of Colorado Boulder… these were people writing comics for the first time and I was pairing them with illustrators. The problem is when you go out and talk to parents about it, and they assume it’s funny. It’s a comic book. Well, no, there’s real history here. That’s one of the main challenges. Another challenge is compressing all the stuff these historians give you into a comic story. I talked about Dr. Anderson. She wrote a 600-page book on free-range animal husbandry, which is one of the key things that started colonialists fights with the natives.

I wrote her, and she had no idea who I was, and asked, “Have you ever thought about adapting this 600-page tome that you wrote to a 5-page comic book made for kids?” She responded, “Who are you again?” So one of the things I begin to try to get around this problem is simplifying the work and using the visual representation of comics and language to show how it can work. One of the big issues between the colonists and the natives was language barriers, so instead of actual text, I use iconography so that we know the characters are talking about, but also can see that the other characters do not.

We did a story about the very first slaves that were brought over to New England on Maverick Island. There was this big language barrier where people didn’t understand what these individuals brought over from Africa were saying. We once again used iconography to show this big issue within slavery, where people couldn’t talk and communicate.

The other problem I talked about is when parents and educators say this is just a comic book. This is where I went back to the Charlie Brown Encyclopedia set and I tried to put in as much as possible that was supplemental and text-based.

People seem to look at text and think it’s more real than comics. So for every story we did things like Spotlight On featuring subjects such as effigies or characters that we couldn’t do full stories for. The last part is showing our work. So for every book I’ve ever done, I always put the bibliography and notes in. For the very first volume of Colonial Comics, we had to go to primary sources and worked with archives, referenced ever story, did book guides and I think that was the way we got around the parent or teacher saying, “Comic books can’t be non-fiction.”

Ben Towle: Do we have any questions from the audience?

Audience member: On the continuum of the most-creative hand-lettered graphic novel and the standard comic book, is serialization the main difference between the graphic novel and the comic?

Kevin Panetta: It’s the length and then serialization as well. Our Zodiac Starforce book, people would call a graphic novel, but it contains the four comic books. Comic books will generally come out on a monthly schedule and be 20-30 pages while a graphic novel can be anywhere from 56-500 pages. I have a graphic novel coming out next year that’s 351 pages long; I apologized to my artist. It is romance, a coming of age story that takes place in a baker, and it’s actually drawn by Paulina’s sister who lives in Australia. We’ve been working inter-continentally and it has a lot of baking and recipes in it. It’s a really cute romance. I’m really excited about it.

Audience member: Have you personally tested all the recipes?

Kevin Panetta: I tried some of them and some of them turned out horribly, but I assume that the characters in the graphic novel are better at it than I am.

Audience member: If I was looking to make a graphic novel, or a comic series, is there any way for a writer to find an artist, or vice versa?

Paulina Ganucheau: Social media.

Ben Towle: It’s worth pointing out that some cartoonists work completely on their own which is what I do, and some don’t and pretty much everyone here is working in combination with somebody else.

Paulina Ganucheau: Again, I would say social media. Twitter has a great community of comics pros and is super-easy to communicate and connect with people, and grow with people. Some of my best friends I’ve met through Twitter and some of my biggest jobs have come through Twitter like my first connection with Marvel, or some of my IDW work, they’ve come from talking with some on Twitter. That’s all it takes. Be nice, be kind, and try to meet people.

Kevin Panetta: I do feel that when you’re starting out, it’s good to work with people on your level, who are also starting out. A lot of people will say, “I want Frank Miller to draw my comic that I wrote.”

Paulina Ganucheau: It doesn’t work like that.

Kevin Panetta: We were both starting out at the same time, and you come up together and create a peer group, and it’s much better than trying to work with your idols, because they’ve got plenty to do.

Jason Rodriguez: I came in doing anthologies and right from the start I had some great artists working on them. I went from knowing zero artist to knowing a rolodex full of artists. When I first started, especially coming in as a writer, I set aside 15 minutes a day to find someone online … through their portfolio or whatever… and write them a complimentary note. Not “Hey, I’d love to work with you,” but “Hey, I really love your work. How did you do this?” I literally did that every day for about 2 years. I wrote 700 some-odd artists and that’s how I built that rolodex of people that I knew. Most people never wrote back, but other people formed live-long friendships and I’ve used them in every single book.

Audience member: My understanding has been if you’re an artist, it’s quite easier to find people who have ideas to write about, but if you’re a writer it’s much harder to find an artist looking for writers, because most artists also have plenty of ideas that they are looking to do on their own. If you’re a writer, even artists who don’t have a track record, are going to be hard for you to find to work with. Is that roughly correct?

Kevin Panetta: Yes, I think that’s true. Also, drawing comics is a lot more labor-intensive than writing comics. I can write a few comics in a month, but a typical schedule for an artist would be to draw almost 30 pages in a month and that’s a lot of work. A page can take anywhere from 10-20 hours depending on if you’re just doing the pencils or if you’re inking and coloring it as well. For that reason, I think artist’s time is a little more precious that writer’s time, and like you said, a lot of artists have their own ideas. As a writer of comics, I feel lucky that any artist wants to draw anything that I write, because they could easily write their own stuff. But some time you have a good vibe with an artist and you do work better together than you would separately.

Paulina Ganucheau: A lot of the writer’s goal is to make the collaboration work. You need to do a little more legwork because the artist has so much to do.

Kevin Panetta: Yeah, I wrote this comic, but who do you think wants to draw it? Her.

Paulina Ganucheau: Me. And I think that’s one of the best things about Kevin as a writer. He’s a chameleon with all of the artists he works with and I really appreciate that quality in a writer. And just listening and being open. It takes two to make a comic especially if you’re a writer or an artist. I don’t like the weight that writers take from artists a lot of the time; it should be even because we’re both doing it.

Jason Rodriguez: To highlight that, I think part of it is the language you use. If you approach someone and say, “I have a comic I wrote and I would like you to draw,” all of a sudden that’s not a collaboration, that’s a work for hire relationship, hiring an employee.

Paulina Ganucheau: It’s one-sided.

Jason Rodriguez: But it should be a partnership more than anything else, and you should say, “Hey, I like your work. Would you like to do something together?” is a much better way to approach someone.

Paulina Ganucheau: Yup, yup. It’s collaborative

Kevin Panetta: Everything I do is a collaboration. I’ve never written a script without knowing who the artist is because you want to write to their strengths and you want them to be a part of the process from the beginning. I think better comics turn out that way.

Audience Member: What are some of the comics that you have read recently that you’d recommend?

Jason Rodriguez: Probably the easiest answer right now is March. We’re all DC people so that’s an important one. I’ve been picking up a lot of minicomics because I’m working on some new projects, and I found this great one that I just love. It was explaining the concept of fear to new immigrants. It’s done over an open license so you can print it out for freeand give it to people. I’m trying to push more towards that, so I’m looking for comics in that vein now.

Paulina Ganucheau: As far as new comics, the new Runaways from Marvel is super-fun and great. My friend Kris Anka draws it and he’s amazing. I’ve been really into Snotgirl by Bryan Lee O’Malley and Leslie Hung. It’s so quirky, and interesting, and unique in its own way. But honestly I’ve been reading a lot of classic manga. A lot of Ranma 1/2 and Oh My Goddess! – classic manga stuff.

Kevin Panetta: I just read a really good Regency Romance coming out soon called The Prince and the Dressmaker. It’s about a prince in in a kingdom who just wants to make clothes, and about him secretly making clothes for a fashionista who lives in Europe in the 1700s. It’s beautiful and amazing. That’s the best thing I’ve read recently. Also Boundless which is a collection of semi-horror stories by one of my favorite artists Jillian Tamaki. It’s really interesting, almost like the Black Mirror show. One of the stories is about a girl who finds an alternative universe version of Facebook where everybody’s living a different version of their life and she becomes really obsessed with it. I love all new Wolverine and X-Men. I work at a comic book store so I probably read 40-50 new comics a week.

Shannon Gallant: The only book I’m really following is Wayward by Jim Zub and Steve Cummings. The thing I like about it is that it’s about a character who’s half-Irish and half-Japanese and she has these mystical powers. The nice thing about it is that the first half of the book is set in Japan, and the next half is set in Ireland, but what’s nice is at the end, they put a lot of information about yokai, Japanese demons and ghosts – factual information written by experts on Japanese or Irish folklore. So you can actually learn, after reading it and going, “What the hell is the guy talking about?” It’s really great and I think it’s a nice way of getting kids interested in folklore by setting up this almost superheroish-type adventure but then giving them factual information.

Kevin Panetta: I think Jim Zub actually went to live in Japan for a while.

Shannon Gallant: I know he’s been there a lot. That’s probably my favorite, but I’m reading old manga. Gegege no Kitaro is all about yokai and I love that.

Mike Rhode: I’m asking the comics will break your heart question of, how many of you can actually make a living in comics, including you Ben?

Ben Towle: I do not make my living solely doing comics. I teach at the Savannah College of Art & Design (SCAD). I teach online.

Shannon Gallant. I do. My sole income is from comics. I used to work in PR and advertising so I still do some freelance for people that know me from that, whether it’s storyboards for video shoots or spot illustrations, but predominantly it’s from my work in comics.

Paulina Ganucheau: Yeah, me as well. I’m full-time freelance. It’s hard but it’s rewarding. You can do it. People say you can’t, but you can do it.

Kevin Panetta: I’m part-time. I had a full-time retail job at the comic store, but I cut down to a few days a week now, and spend more time writing than working in a comic store. I still like doing both, and having a part-time job is nice because freelance isn’t as dependable as working each week.

Ben Towle: Yeah, working in a comics store is at least related. I teach comic classes, so I’m not ‘woe is me.’ I’ve worked in factories and stuff so I’m very happy to be drawing comics some of the time and teaching them the rest of the time.

Jason Rodriguez: Believe it or not, publishing historical anthologies with small to medium size publishers and 30 people in a book does not make a lot of money for a person. I have two jobs, basically full time, but this is the first year where I did pretty good in comics. We mainly did it through getting grants. I love grants. What a good thing. I’m actually mathematician by day and I do a lot of

sci-fi writing also, and this year, I did a Kickstarter for a children’s book about particle physics.

Ben Towle: On that note, we’re out of time.

Ben Towle: Kevin?

Ben Towle: Kevin? Shannon Gallant: Larry Hama, who was the writer on G.I. Joe since it started at Marvel back in the 80s when I was a kid (although it took a hiatus for years), is still writing it. Larry has a habit of trying to do things for friends and make them happy. Apparently he had a friend in Ireland, and he set a scene in Dublin. It’s a ride around the streets of Dublin. Well, I’ve never been there and I don’t know what it looks like. In the old days before the internet, you had to have a morgue file [of pictures torn out of magazine and newspapers to see how something looked when you had to draw it]. I was growing up when we didn’t have the internet so I was building a morgue file. If that was the case now, I would have been screwed because I didn’t have any pictures in the morgue file of Ireland at all, but thankfully now there’s the internet. So what I wound up doing was getting on Google Maps and ‘driving’ myself through downtown Dublin. The restaurant where the truck is crashing in and the barrels are flying everywhere is based on an actual place. These are shots of traffic from Google. I basically planned it out. Larry had this big elaborate description of what was happening, but I just had them drive around in a circle. If you follow the Google Maps, you would just see a big square in the middle of the page, but that was how I solved the problem. I tend to overdue all of my research on things like this, especially for sets and detail work. I found all these shots, and then I only used two. I got around 500 reference photos off Google Maps and I think I ended up using five or something insane.

Shannon Gallant: Larry Hama, who was the writer on G.I. Joe since it started at Marvel back in the 80s when I was a kid (although it took a hiatus for years), is still writing it. Larry has a habit of trying to do things for friends and make them happy. Apparently he had a friend in Ireland, and he set a scene in Dublin. It’s a ride around the streets of Dublin. Well, I’ve never been there and I don’t know what it looks like. In the old days before the internet, you had to have a morgue file [of pictures torn out of magazine and newspapers to see how something looked when you had to draw it]. I was growing up when we didn’t have the internet so I was building a morgue file. If that was the case now, I would have been screwed because I didn’t have any pictures in the morgue file of Ireland at all, but thankfully now there’s the internet. So what I wound up doing was getting on Google Maps and ‘driving’ myself through downtown Dublin. The restaurant where the truck is crashing in and the barrels are flying everywhere is based on an actual place. These are shots of traffic from Google. I basically planned it out. Larry had this big elaborate description of what was happening, but I just had them drive around in a circle. If you follow the Google Maps, you would just see a big square in the middle of the page, but that was how I solved the problem. I tend to overdue all of my research on things like this, especially for sets and detail work. I found all these shots, and then I only used two. I got around 500 reference photos off Google Maps and I think I ended up using five or something insane. Ben Towle: Absolutely, if you’re from this area and you’re not going to SPX, you’re missing out. It’s one of two or three of the best indy comics shows that you get. Independent creators, with their own books and not Marvel or DC, are hand-selling stuff, a lot of which they made themselves with silk-screening and stapling. It’s a really amazing show.

Ben Towle: Absolutely, if you’re from this area and you’re not going to SPX, you’re missing out. It’s one of two or three of the best indy comics shows that you get. Independent creators, with their own books and not Marvel or DC, are hand-selling stuff, a lot of which they made themselves with silk-screening and stapling. It’s a really amazing show. Jason Rodriguez: I’m going to focus on my colonial history books. The purpose of these books is to include under-represented narratives from colonial history. When I first sat down with my publishers, I think they were taken aback a bit by how much I wanted to put into this. I had Pulitzer Prize winners of non-fiction writing stories, professors like Doctor Virginia DeJohn Anderson from University of Colorado Boulder… these were people writing comics for the first time and I was pairing them with illustrators. The problem is when you go out and talk to parents about it, and they assume it’s funny. It’s a comic book. Well, no, there’s real history here. That’s one of the main challenges. Another challenge is compressing all the stuff these historians give you into a comic story. I talked about Dr. Anderson. She wrote a 600-page book on free-range animal husbandry, which is one of the key things that started colonialists fights with the natives. I wrote her, and she had no idea who I was, and asked, “Have you ever thought about adapting this 600-page tome that you wrote to a 5-page comic book made for kids?” She responded, “Who are you again?” So one of the things I begin to try to get around this problem is simplifying the work and using the visual representation of comics and language to show how it can work. One of the big issues between the colonists and the natives was language barriers, so instead of actual text, I use iconography so that we know the characters are talking about, but also can see that the other characters do not.

Jason Rodriguez: I’m going to focus on my colonial history books. The purpose of these books is to include under-represented narratives from colonial history. When I first sat down with my publishers, I think they were taken aback a bit by how much I wanted to put into this. I had Pulitzer Prize winners of non-fiction writing stories, professors like Doctor Virginia DeJohn Anderson from University of Colorado Boulder… these were people writing comics for the first time and I was pairing them with illustrators. The problem is when you go out and talk to parents about it, and they assume it’s funny. It’s a comic book. Well, no, there’s real history here. That’s one of the main challenges. Another challenge is compressing all the stuff these historians give you into a comic story. I talked about Dr. Anderson. She wrote a 600-page book on free-range animal husbandry, which is one of the key things that started colonialists fights with the natives. I wrote her, and she had no idea who I was, and asked, “Have you ever thought about adapting this 600-page tome that you wrote to a 5-page comic book made for kids?” She responded, “Who are you again?” So one of the things I begin to try to get around this problem is simplifying the work and using the visual representation of comics and language to show how it can work. One of the big issues between the colonists and the natives was language barriers, so instead of actual text, I use iconography so that we know the characters are talking about, but also can see that the other characters do not.

Ben Towle: Yeah, working in a comics store is at least related. I teach comic classes, so I’m not ‘woe is me.’ I’ve worked in factories and stuff so I’m very happy to be drawing comics some of the time and teaching them the rest of the time.

Ben Towle: Yeah, working in a comics store is at least related. I teach comic classes, so I’m not ‘woe is me.’ I’ve worked in factories and stuff so I’m very happy to be drawing comics some of the time and teaching them the rest of the time.