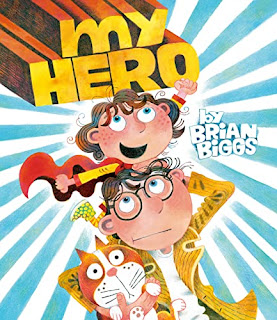

Recently Brian Biggs came down to DC to look at original art at the Library of Congress and talk to the librarians about preserving his own work. After that, he and I met for lunch on a Library patio, to talk about My Hero, his new book about a child superhero. We were joined by Prints & Photographs librarian Sara Duke and my daughter Claire Rhode, a former children’s book seller, who were invited to ask questions as well.

The book’s secret origin

Brian Biggs: Well, haha, you just did. But Publisher’s Weekly

published a capsule description and review.

Brian Biggs: Well, haha, you just did. But Publisher’s Weekly

published a capsule description and review.

MR: Ok, then how did you come up with the idea for it?

BB: The idea for the book was hatched over lunch way back in 2007, believe it or not. I was talking with my friend Tamson, who was an editor for Hyperion and other children’s publishers about the characters I like to write. Both of us had young kids at the time, around seven and five, and I seemed to be wanting to tell stories about kids that age. These little kids who have these rich internal lives separate from the larger world and an absolute belief in themselves that anything is possible. As parents, we don’t really share that belief, because it’s our job to keep them safe. So this little kid, named Jeff at the time, wants to do something and it might be just helping the old lady across the street. But we as parents are like, “Oh wait, look both ways… don't do that thing.“ Or, or in my kid's case, it was walking down the dirt road at their grandma's house to fetch the mail. It's an old house set back in the woods and the mailbox is down this dirt road just a quarter mile away. There's nothing really that can happen to them, but of course, as parents, we can think of 5,000 things that can happen to them. And so, for my kids, their thoughts were, “We're going to go get the mail for mom and dad” or whatever, but we're like, “Don't get hurt, don’t get kidnapped, don’t fall down.” So, this started as an idea, it was just a sketch, a one-inch tall sketch of a book called Jeff Hero. The sketch was a little boy sitting on a hilltop with his bicycle lying next to him and his cape flapping in the wind and his hands on his hips. And it says, in the same lettering that I use here in My Hero, it says “Jeff Hero” coming down from the top in sort of in a Schoolhouse Rock sort of way. Sometimes you do something like that and you think, “Huh, I don’t know what this story is about or what it means, but that's going to be a book someday.”

Years later, actually just as I began work on this actual book, I found a paragraph in the same sketchbook where the kid, Jeff, has found two rocks, and he's talking to someone about these two rocks. At the end of the paragraph, we realize that the someone he's talking to is a bird. So, apparently, there was a talking bird in this story. And I didn't know anything about it. Where did this come from? It was kind of fun to read, but I don't know what it is.

I was on a bike ride about three years ago, where I do a lot of thinking, and I realized that Jeff isn’t Jeff. Jeff is actually a little girl, and Mom's not Mom, Mom is Dad. And that shift made everything fall into place at that point, because for me, this made the story about my own kid, who was going through his own transition. So now the person who I believed to be my daughter is my son. It was that it was during that period where he was announcing his transition, and I realized I'm not giving him his own space to be this person he is. As an adult, I was forcing something else, maybe… I don't know what. I'm still not always comfortable with the whole idea, but you have to back out of the way of a young adult at some point, right? And so, the same way Dad has to back out of the way of Abigail in the book and let Abigail be the hero she truly is, and save him from Purple Octopus. Purple Octopus is all of our fears that manifest however they want to manifest.

There are enough clues in the book so that a kid could convince a parent that Abigail really is Awesome Girl, and this is all a true story; but of course, a parent sees it as merely a metaphor. “Oh, you're still just pretending, and I didn't really get caught by the purple octopus,” but are little clues.

BB: The book begins with a cat in a tree over seven spreads, so I drew this tree seven times. But I must have actually drawn that tree about 40 times, as sketches, as practice, just different ways, different methods, different media, different ways of doing it. This is like performance art in a sense where, when I start drawing these leaves, it’s in real-time with different colored inks set out with water and the way they bleed is important, and I can’t stop in the middle. I would turn off my phone <laugh> and I needed an hour… I'm going to draw a tree and I can't get up. So those are the days I couldn't take the dog to the studio, cuz if he starts giving me a hassle when I'm in the middle of the tree, it would never work. It was strange and new for me.

BB: It's colored ink. The ink is a lot more vivid than watercolor and the Liquitex Acrylic inks are super bright, so I would fill up a little one of those trays, with the little compartments with different colors, and some in the same compartment because I knew I was going to mix 'em anyway, and I could swirl 'em and get certain mixes. Timing when things were going to be dry and when they weren't… this color all bleeds together, but then with the pencil there, I make that leaf finished, in a way that you can’t with watercolor.

MR: So after it's dry, you go back in and differentiate some of the leaves?

MR: It’s a very multimedia approach.

BB: And I had to really be careful around the edges of this orange cat that’s stuck up in the tree.

MR: You said you had normally had not done a process like this?

BB: Well yes, my comics in the 90s. But it’s different so let’s skip my comics for a minute and start with children's books. Starting in 2002, either the work was black and white ink drawings, or if it was color, it was all in Photoshop. Everything ran through Photoshop. So the way I did most of the books that I illustrated was that I would draw it in black and white ink, and then scan it into Photoshop, the inked lines would get color, or else I would add color the way you'd color in a coloring book. Everything Goes is done that way. Those ink drawings exist as black and white drawings, which might be interesting to the Library of Congress, because I always like seeing color work where it's not color, like, “Oh, that's black and white in real life.” And then all that color work in Everything Goes, and all the textures, are all completely digital. Same with Tinyville Town, and all of the books I illustrated. In fact, some of the Frank Einstein books were even drawn completely on the computer, just because of deadlines.

MR: Right. I remember being disappointed about that.

BB: Well, the first book is all analog, but the second through sixth books are digital. I developed a Photoshop brush, a fake virtual brush that I use with my Wacom tablet, that kind of looks like my own way of drawing. It was just that you can get it done so much quicker. And that's kind of when, I think in 2017 or ‘18, is when I just started thinking “I'm so done with this.” I was even drawing sketches on the computer, and there's part of that process that facilitates it, but then also the iPad got popular for illustration. Procreate is the Photoshop-like app for the iPad, and brushes are now marketed as looking like say riso-printing, or looking like screen printing, or watercolor, or looking like old commercial art from the fifties and sixties, and it's unbelievably realistic. You can't believe how good it is. The texture of the paper is there. It's remarkable. And of course, me being the contrarian that I am, I said as the world is moving one way “Wait a minute. I'm not flying in that supersonic airplane. I'm going to take that horse and buggy.” But I also wanted to know, after drawing 70 books, I wanted to know, “Can I do this?” I always was envious of looking at Sendak’s work, or Scarry, or Mary Blair and how they managed to do that with these old proper art supplies. But also, even looking at today's artists like Beatrice Alemagna’s and, so many European illustrators, they do a lot of beautiful work. When you see Beatrice Alemagna’s actual art, her drawings are enormous. There are pieces of cardboard glued to paper, and pencil, and she's got pastels everywhere. And I think, “now that's an artist, I want to go home with my hands dirty every night.” When The Spacewalk, my previous book, didn’t sell very well, I said, “Screw it. The pandemic pushed everything up a year, I have all the time in the world now, so I'm going to do it the way I wanna do it.” And I taught myself to do it.

MR: You had done coloring prior to children’s books though?

BB: Yes, but more of a mechanical screen print, layered style. Using separations. That was the way I'd done color, like the posters from the comics days, and even a lot of illustrations that I did for commercial work, and Tinyville Town was colored this way. Tinyville Town only used seven actual colors. The purple and the yellow overlaid made a brown. When you look at the layers in Photoshop, it looks like screen print layers. There will be a purple layer and a yellow layer and a transparent overlay effect called multiply. It's like you're looking through film. So for ground, I might use a rough Photoshop brush and do the purple, and then a rough yellow on the layer beneath it. The two together create this textured brown, but you can still see the purple and the yellow in between some of the spaces, which for me is really fun, but there's not an eight-year-old in the world that cares. So all it does

is just kind of create a look and a feel. The shadows in Tinyville Town are a layer of one light blue that are drawn on, and so if it goes over a white area, it's blue, but if it goes over the yellow, it creates a green. But that's the way, just like these shadows around us aren't gray, they're blue because of the sky. It's just a light theory thing, but it looked like the way I wanted it to look, so that's the way I created those. Very much not like painting. If they were drawn, before Photoshop, if they were done non-digitally, they would be layers of what I saw today in art by Seymour Chwast, those overlays of red rubylith. These colored films would be photographed just in black and white. Then when they're run through the press, the four color press, they would have X percent of magenta or X percent of cyan or whatever. So that's the way my brain puts images together normally. This new book has been, to me, a revelation. I mean, it's the most traditional looking book I've made, but it's the one that was the most complex in the way of planning it out and figuring out how I was going to do it. And I love that these pages exist as actual paintings in a drawer in my studio. You can look at a page and it looks like this printed page. No parts of it are separate. The lettering is not separate. That is a painting.MR: You did the lettering on the artwork?

BB: In most cases, but of the small text lettering was done separately.

MR: The stuff that looks like more like typography, even though you hand lettered it?

BB: Yeah. The lettering was about a quarter inch tall, so my eyes didn't completely break out of my head, I shrunk it down for the book.

MR: Is the city based on a real city?

BB: No, it's just a city. It's a kind of like Power Puff Girls always had Townsville, the Incredibles have Metroville It’s this generic town I just try to draw with a fake-looking toy Empire State Building. Using different colors and playing around with drawing the buildings, but it's not based on any city, just big old buildings.

MR: I asked, because you have been in Philadelphia for 20 years, a long time to be in one place when you wandered the world when you were younger.

BB: Right? For my first 22 years, I lived in 6 cities. In my thirties, I was in San Francisco mostly, and then moved to Philadelphia in 1999 from San Francisco, and I've been there ever since.

MR: When you were a cartoonist, you were in Paris?

BB: Yeah. I grew up in Little Rock, Arkansas until I was 11 - born and raised in Little Rock, and then we moved to the Houston area from age 11 to 17. I went to a town called Denton for one years of college at North Texas State University, went to New York City to Parsons for sophomore year of college, Paris for junior year, back to New York for senior year, then back to Paris for a year to work. That's when I drew Frederick and Eloise. I’d discovered Tardi and the great French cartoonists, and again, had found myself unemployed with nothing to do. I had 5,000 bucks in the bank, drew this book, spent the money, and went back home to the Dallas / Fort Worth area. I was there for two years and in ‘93 moved to San Francisco where I met my kids' mom. We eloped in Vegas, then moved to Philadelphia because she was from Trenton, NJ and we wanted to be near family. 22 years later, I've seen the Phillies win the World Series, I've seen the Eagles win the Super Bowl, and I finally accept I live there. I'm still a Razorbacks fan. I still follow Texas politics, which is a sad state of affairs. But when the Eagles won the Super Bowl, I'm out in the street crying and hugging strangers. “Okay, I live in Philly now. Wow. I accept it.” My kids were in my living room that night, my wife, and my ex-wife and my kid's stepfather... We had 25 people in our living room and from that part of my life and there's so much emotion about a stupid football game, but it's the first time the Eagles have ever won. And that city loves its sports. We were out on the streets three days later for the parade in the mud. It was 25 degrees and it was an amazing experience. And you just embrace what it is. I mean, I'm not from Philly, but I'm from Philly. However, in my neighborhood I'll always be a yuppy because I've “only” been there 22 years. I lived in one house 11 years and moved a few blocks away for now another 11 years. But for the lady down the street who has lived there her whole life, as far as she's concerned, I'm just an interloper. That's one of the reasons I love Philly -- the crazy racist neighbor next door. <laughs>

MR: This children's book just dropped May 3rd. Let's go back to the artwork on here. The dad definitely looks like Clark Kent on the cover.

BB: It's been mentioned. Yes. It was not intent of mine, but it may be subconscious. When I read a review on Book List, it said Dad has a Clark Kent-resemblance and I thought, “Oh, yeah, he does.” I love it when someone points something out to me that is not obvious, but it was obvious to them.

MR: You didn't do that on purpose, but you did do something special about the book cover?

BB: Yes, there are two covers. If you remove the paper dust cover off of the hardback cover, you see the superhero comic book-type cover underneath, and that was definitely planned. Later in the book, there was a scene where Dad, who is not Clark Kent, yanks his his shirt off to reveal the superhero “A” underneath. That is the Clark Kent moment. The covers go from the dad-daughter relationship where he’s carrying her, to one where the daughter is in charge and she's the main character.

MR: Is the “A” for Awesome for everybody in the family and not just Abigail, if Dad has it on his shirt?

BB: It’s only for Abigail. Dad has it on his shirt too because he is revealing that he does, he really does truly believe in her.

But it’s funny, because her name has been many things. It was Theo for a long time and she had a “T” emblem and I think it was changed because we couldn't think of a modifying adjective. Before that it was Samantha. She was Sam. The problem with the “S is the legal team at Penguin came to us and said, “Excuse me, but there's a famous trademarked “S” on a shirt in red and yellow that we can't really challenge, so we need to change the name.” And I saw that coming a mile away, but just thought I'd push it. Luckily, I hadn't started on the artwork yet. We had changed “T” to “S” as Super Sam is easy and obviously suitable. “T” -- was it Thunder Theo? What's that? Terrific Theo doesn't work. So I asked some little girl I know, maybe my niece, “What would your superhero name be if you had one?” And she said, “Awesome Girl.” I realized it doesn't have to be Super Sam, or Awesome Anna. It's Awesome Girl. And that works really well.

“A” became Abigail and Awesome Girl, and Awesome Girl -- there's something unsophisticated about it. It's like a little kid. “Oh, Awesome Girl!” That works really well for me. The dad happens to have a shirt too that says “A” on it, but that's part of the question. Is this real? Is it not real? Why would dad have that shirt? It's because he believes in her, and he rips his white shirt off, and there it is. There's proof of his believing in her. There's another double entendre. What does that mean to believe in your kid? Is he really believing his kid or is he believing in his kid? It's not a book that I could have written before I had my own children.

Her towel becomes a cape, Dad's folding her pajamas and her towel so when she has this moment where the cat accidentally kicks the plastic octopus out the window, and then suddenly says, “Look there!” (which, by the way, is the same lettering as the very beginning). It's very easy to say, “this is all in her sitting in the bathtub, with her angry imagination of having this fantasy of her dad getting kidnapped.” Originally, when it was “Jeff Hero,” Mom was kidnapped by a robot, and the whole story was what does Jeff have to do to save his mom from a robot? When I spun back around to her, a robot is so boring in this case, but having it be a purple octopus that started out as a bathtub toy became kind of this harmless polarity. How do you make an octopus both friendly and menacing at the same time?

MR: The villain Octopus still has a smile, but it's got lowered slanted eyebrows and the cat now wears a mask.

BB: The eyebrows are everything, and he's also really big.

Claire Rhode: That’s like Perry the Platypus from Phineas and Ferb. They own a platypus, but he's always sneaking behind their back to fight his nemesis Dr. Heinz Doofenshmirtz. It just seems like your original idea for Harry is similar, because the kids stumble into Dr. Doofenshmirtz and end up battling him. But there’s always the platypus in the background as the secret agent.

BB: I don’t know the cartoon, but I liked the idea, like I was saying originally, of Harry being the puppet master behind everything. I couldn't dive in deep enough though. If this was a bigger book, then I could dive into him.

CR: You didn't have several seasons like a tv show.

MR: Your agent didn't push you to make this more like Dog Man, or make this a series and a smaller size?BB: In fact, that's an interesting point with this book that I've wondered about a lot. This book was the unnamed second book of a two-book deal. They bought The Space Walk and another picture book, and to Penguin's credit, they never asked me what the other picture book was going to be. It was just, “Okay, we're done with The Space Walk,” and right before COVID, Kate, my editor at Dial, says, “What are you working on next?” I showed her some sketches that had the lettering and little boy saying, “Who is that? How is she so awesome?” And Kate was always saying “We’ve got to get that little boy in there.” I responded, “He's not in there, but the lettering is there. So that works.” This really never had to be pitched as a book, and I don't know if it could have been. I don't know if I could have explained at the time, because I would've had to finish it more. Luckily it really was allowed to kind of grow out of whatever into something else, and I always appreciated that.

MR: Let me ask two process questions. One's about layout and one's about your sketchbooks. So do you thumbnail the book? Do you write the script? Or do you do one page at a time and get surprised?

BB: <Laugh> It's all three actually. At some point I start thinking of what are signposts in this story. In this case you had the tree; I knew there was going to be a tree section. For a while, it was going to be ten spreads and it got cut down to seven, thank goodness. Then I knew there was going to be the bathtub scene. I remember the revelation of thinking, “Oh my gosh, some of it's told in comics -- this whole fantasy scene in comics.” Both this book and Spacewalk follow a pattern that Where The Wild Things Are established, which is a kid whose angry at parents and then going into a fantasy world. For The Space Walk, it's “I want to go out and take a walk,” and the parents/ground control say, “You have to clean your room.” He's frustrated, but he's an astronaut, and it's ground control talking. And then he is allowed out on his walk and he meets the monster of Where The Wild Things Are

, but in my case, it's that alien with the wiggly legs. He makes friends and then comes back home and says, “Can I go out again tomorrow?” and they say, “You have do your astronaut duties.” Well, that's one way of looking at Where The Wild Things Are. In My Hero, Dad is a real instigator. In Where The Wild Things Are, Max's mom just says, “You have to go to your room, because you're bad.” So Max sits in there and fantasizes about this monster world.So this is much closer to that, where she's in the bathtub with her arms folded. In fact, originally, she was in bed and Dad says goodnight to her, but my editor -- and this is where editors are worth her weight and gold -- said, “Dream sequences, meh, it's been done a million times.” In fact, Where The Wild Things Are is technically a dream sequence. She asked, “Is there another place you could have the girl, at the time Samantha, be to have this anger?” I responded, “Yeah, the bathtub, that totally works.” Because Dad leaves her and says, “All right, dry yourself off and come on, I’m making dinner. She's like “Grrrr.” She's angry, so she has this whole fantasy in the bathtub. Instead of the land of the monsters where Max goes, hers is this world with her and her cat saving the day. In fact, this is an homage to Sendak. When at the end, Max walks back into find the soup in his bedroom. I drew her, and it is exactly the same drawing. It's just it's Abigail instead of Max and so far, no one's caught that. I doubt anybody ever will, but I like it and I'm happy it's there. The resolution at the end, where Max gets soup and she gets spaghetti, I love that sort of thing.

So there were sign posts, establishing the rhythm of this happens and that happens and then this other thing happens. Then what I do is I'll go in and focus on just the first part and write it completely out without any editing. And then the second part: what happens the bathtub scene?

And then at some point I will write the whole story as just text -- the dialogue, the action as if the story's being told. My editor needs that to basically to run it through copy editing. They've got their whole channels that they send it through at Dial. In in my case, it's always sort of unspoken that this may or may not be the final. Things are going to get changed and I don't write books that way. I don't write books in text. Actually, it's an interesting thing, because as an illustrator, when I get a manuscript by another author, there's almost never stage setting the way I write mine. Like there will never be a “Abigail poking your head up when around the door” -- it would just be “time to eat” and then I figure out what that is. If an author starts writing that kind of stuff, I don't want to deal with it. I I'll ignore it. I'll cut it out with the Word file and throw it away because want to stage it myself.

MR: Although that is sometimes a traditional way of people working on comic books, like Alan Moore famously sketching every little thing in for his artist. Whereas the Marvel method is more like “Here's five words, go draw something, figure it out.”

MR: We're both in our fifties and when reading comic books in our youth, the words just reinforced what was drawn.

BB: The only narrative part of this book is, where she's in the bathtub and I don't need to say, “Little hero Abigail thought to herself,” because clearly that's what she's doing. “As he went to make dinner,” that sets up later on, so that's important. I'm not saying he's folding her clothes., I have a good editor for this stuff, because she was saved me from myself where I would've said something like “Abigail was standing on the toilet in the bathroom as her father ran a bath.” Delete it. It's already there, you know?. I've never worked off of a strip comic script before. I'm doing a Little Golden Book right now where they actually send a script on a page with what is going to be on each page. You know, green garbage truck here and over here, you see a neighborhood full of people of different colors.

MR: It's more of an illustration job, and less of a creative job in some ways.

BB: Very much so for Little Golden Books. Work for hire jobs are the same way, but I don't do them anymore. When I used to, I’d get them very methodically structured. When I was last here in 2017, the book that I was reading with Mac Barnett was one of the best picture book scripts I've ever illustrated because it had one piece of description. I’ll give you two examples. Mac wrote, “It begins on the bottom floor of a tall, multi-story building.” And then it says, “A boy woke up” and the story begins and everything else in illustration was up to me. He didn't describe anything. The entertaining part of that book was figuring out how to, in a horizontal book, tell a vertical story. The structure of that book is one that I've given presentations on. I did it with color coding, because it has to build upward through the book and the whole layout is done with these color blocks where you can see literally the steps as the elevator goes up the book.

The second example was a book series called Brownie and Pearl about a kitten and a little girl. The opening line is “Brownie and Pearl are stepping out.” I knew from the rest of the script that they were going to a birthday party, so what is this opening illustration going to be? There is so much in that line. What does that mean for a little kid and her kitty to be “stepping out?” It’s fancy, right? They're wearing fancy clothes. The cat has a flower in her hair, and they're they got balloons and what’s a three-year-old look like when she steps out? She's got a little boa around her neck going to this birthday party. That was a lot of fun, because that's such a line that I would've never written. But Cynthia Rylant wrote it and she's such a master storyteller that she didn't give more information than that at all. It could be set in the country. It could be set in the city, but I'm thinking “A little girl in a city neighborhood going to a birthday party,” you know? Finding words that evoke something either make the illustrator do something or help my own illustrations along. I'm a much stronger illustrator than writer; writing is always a challenge for me. But for a book like this, it's always fun to explore what are things the words can do that pictures can't or vice versa. I think I found the balance in this one.

BB: So the first two options are both yes. The third option that you didn't mention is I sometimes will go through a sketchbook upon finishing it or even after doing the page and scan certain pages and drop 'em into the books folder on my laptop, which has about 50 folders. I'll title things that maybe I'll work on later. There's one called ‘Bernard Barnard,’ which was in fact Marc Weidenbaum’s title idea. How many years ago? 25. That idea's been sitting in that folder for 25 years over probably 15 different computers and two kids. Will it ever get written? I don't know. I don't know, but boy, I've got some ideas. I created a new folder this morning called “frog, stinkbug, and fish” because that's the manuscript I just wrote.

BB: That idea also came from a sketchbook from 2012 where I had just a list of names like lucky dog, cool cat, stink bug. Those to me evoke a little book about a cool cat or a lucky dog or a, a dirty dog or things like that. One was called bird songs and I just knew that list is absurd, but I think I got on Facebook and asked for more and people gave me names. So in this particular case that has been in the back of my head for years. I never forgot about the bird, lucky dog and all that, but it's a matter of kind of thinking “what is it?” Someday, I'm out on a bike ride or going for a run or just taking a shower and might go, “Oh!” This happened on Friday. I sat down and just started writing. You put a stink bug on a leaf, eating piece of fruit and a frog on the spot. What happens? So that's kind of where that idea comes from although the plan wasn't there. I keep scans of sketchbooks. I keep sketchbooks that are all dated. I use those little Moleskines. I've got about 20 of them all on a shelf going back about 16 years.

Sara Duke: What percentage of your sketchbooks are drawings and what percentage are text?

BB: ha ha. This is somebody who's

obviously seen sketchbooks, because they're mostly grocery lists, or things I

need to do today. It's probably 60% writing, 40% drawing, but the drawing is

only 10% decent. A lot of times it's just a quick knockoff where I don't even

know what I was doing, but every now and then there'll be a moment of

inspiration. I'll get six or seven pages from these little tiny sketchbooks.

BB: ha ha. This is somebody who's

obviously seen sketchbooks, because they're mostly grocery lists, or things I

need to do today. It's probably 60% writing, 40% drawing, but the drawing is

only 10% decent. A lot of times it's just a quick knockoff where I don't even

know what I was doing, but every now and then there'll be a moment of

inspiration. I'll get six or seven pages from these little tiny sketchbooks.

MR: Can you tie it into climate change? Do you have a hook for your next book?

BB: Oh, absolutely. Yeah. And COVID as well. In fact, I didn't know what the story looked like in my head until COVID and I started seeing playgrounds with police tape around them. People are wearing masks in stores. Remember in May of 2020, it was so weird to see people wear masks? And I was thinking, what do five-year-olds think of this? And now they're the ones most used to it of anybody.

SD: They don't remember before time.

BB: Yeah, they don't remember before that. So I’m just loving pencil drawings again, which goes back to the first things you draw with are pencils, and then you learn all these fancy tools. I’m going back to these pencils, but I have this. I carry this fancy thing around with me [showing a large rolled pencil case]; there's one of everything in here and I've got another one of colored pencils at the house. I've become a pencil nerd. I started with Blackwings about two or three years ago. I was at a gift shop in Frenchtown, New Jersey and found these Blackwing pencils and then Musgrave made in Tennessee right after that. And then these guys, this is a big lead hole [showing a big soft pencil lead] Look at that thing. I mean, I love it. It's so much fun to sketch with. That's where these drawings all begin -- real loose with this, and then I'll go in with the sharpen pencils and touch it all up. Yeah, those little sketchbooks are almost all text in some cases.

SD: I've seen sketchbooks and they're most always text. And I always wonder… I always walk around with a pencil. I'm a nub person.

BB: My notes app has become more text now. That's where a lot of my lists go -- in my notes app on my phone.

SD: I always wonder, because sketchbooks tend to be as much, if not more, text than pictures. Do artists still think in text first? Or do you think in pictures first?

MR: You said you had a stock of Frederick and Eloise. Are you willing to sell it to people who read this far in the interview?

BB: It's on my website. The book is on Amazon, but I can't imagine they have any in stock. I don't know how that would work because I don't know who they'd be buying them from. Fantagraphics doesn't have them and it’s the same with Dear Julia. I don't think it's in print anymore. About three years ago, somebody wrote me a letter and said she has all but number three of the Black Eye edition of Dear Julia. And so I sent her a copy of number three and she wanted to know how much I was like, “Are you kidding? You have three other ones. And this cost me nothing. Venmo me five bucks for the shipping, whatever. I don't care.” And that's why I'm not Elon Musk with Tesla money.

One time somebody came to a

Barnes and Noble, where I was doing a book signing and her son was getting one

of the Tinyville Town books signed. And she had a stack of Frederick

and Eloise and Dear Julia too, the Top Shelf and the Fantagraphics

book. She says, “I couldn't believe you're the same Brian Biggs.” I replied, “I

can't really believe it either.” Sometimes I wonder if I am, because those two

books are from different lives. It's a different life. Those stories come from

such different places, it's a strange thing sometimes.

MR: Any other questions? All right, it seems fitting to wrap it up on “It's a strange thing sometimes.”

Here's more cats, trees, and alien climate invasions...

|

|

No comments:

Post a Comment