This is a bit dated now, but I think it still contains information of interest. I'll post the entire thing over the next few days.

The Commercialization of Comics:

A Broad Historical Overview

Michael G. Rhode

International Journal of Comic Art, 1:2 (Fall 1999)

Since their creation, comic strips and books have been licensed by their owners for use by other companies, and also merchandised as various products by their owners. Commercialism may be inseparable from the art form. Comics are, in Spiegelman's memorable phrase (1994: 106), "the bastard offspring of art and commerce," possible as a mass-produced commodity only within the past century and tied strongly to advertising and selling newspapers. It is important to remember that people want to buy merchandise showing a favorite comics character.

This article will examine some of the broad trends in commercialism with noteworthy historic and recent examples. As entire books have been written on the merchandising of single characters1, only high points of commercialism will be touched on.

For our purposes we can begin with the creation of the Richard Outcault's Yellow Kid, generally-accepted as the first recurring comic strip character, in 1895. As Witek pointed out in his study of the history of comics criticism, recurring characters have long been accepted as part of the definition of a comic strip. In fact, they are, as he also notes, a necessity for merchandising a strip (Witek, 1999: 6). Possibly the only exception to this is Charles Addams' gag cartoon characters, which were adapted to television before being given names and personalities.2 Dotz and Morton explained the need for recognizable characters starting concurrently with the rise of newspapers:

With the Industrial Age came mass production and mass transportation. Mass production enabled manufacturers to produce their goods in quantities previously unimaginable. Mass transportation gave them the wherewithal to disperse these goods on a national and eventually global basis. People started recognizing products by their packages, and it didn't take manufacturers long to realize that mnemonic devices, such as logotypes or distinctive characters, might help single out their products in the minds of consumers (Dotz and Morton, 1996: 8-9).

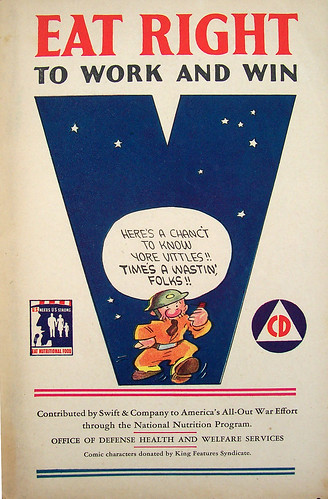

Pre-existing recognizable comics characters with built-in popularity, recognition, familiarity and sometimes a participatory vicarious lifestyle quickly proved to be a powerful commodity. The Yellow Kid initially helped to sell the newspapers he appeared in, but was soon used to advertise cigarettes, chewing gum, and yeast.

Figure 1 Marge's Little Lulu preferred Kleenex tissues in this September 6, 1954 Life Magazine ad.

Figure 1 Marge's Little Lulu preferred Kleenex tissues in this September 6, 1954 Life Magazine ad.

Advertising and comics have had a long and fruitful association. Some characters and comic strips were created purely as advertising vehicles (Goulart, 1995). Comic characters such as Tillie the Toiler, the Katzenjammer Kids, Skippy, Little Lulu (Figure 1), and Li'l Abner acted as celebrity spokesmen for products that they "used" while Snoopy still sells life insurance (Gordon, 1998: 89-105; Lowe, 1997). Recently, borrowing from the movies, Chaos! Comics began selling advertising space through product placement directly in their comic book stories ("First-Ever", 1998).

A major advantage to licensing and merchandising is the continuation of profits long after the initial concept is created and frequently long after any original works are still being published. Superman is sixty years old but is still making money for DC Comics and corporate parent Time-Warner. Companies have taken note of the long-term power of licensing since the 1900s.3 By the 1990s, the current business trend of "branding" had led to extreme levels of commercialism. Including DC Comics and Warner Bros.' animated creations, Warner Bros. Consumer Products currently has 3,700 licensees4 (Warner Bros., 1999). Few other art forms have demonstrated such long-term earning power. Even characters nearly defunct can be revived for a new audience as the 1996 Phantom movie showed. A modest success in the United States, it performed better in Australia where the character is a national icon. Bob Fingerman, a comic book creator, sees this as working against the artform:

Comics used to be the main item, and T-shirts and baseball hats and toys were the side merchandise. Now they're the primary merchandise, and the comic is like this little nothing entity that, in a way, is to the detriment of the company. Eventually, what's going to happen, as far as I'm reading the writing on the wall, is comics will disappear altogether, because the only things that are really valuable now are the properties, the characters. And the characters are being exploited in other media. You've got CD-ROMs, you've got video games, movies, television, animation, toys, etc. That's where all the money is being made (Worcester, 1998: 101).

Comic Strips

In America, comic strips are usually owned by the syndicates that distribute them and comic book characters are usually owned by their publisher. With break-out successes, a large amount of money can be earned. Cartoonists, unsurprisingly, have not been adverse to getting rich through the exploitation of their creations. Outcault became wealthy because of his Buster Brown. He was never the sole owner or copyright holder of the Yellow Kid, so much of the licensing did not profit him (Gordon, 1998: 32). He did defend his rights in court to Buster Brown. He lost when the court ruled that while an individual cartoon could be copyrighted, the general characters could not; additionally the New York Herald which employed him to draw Buster Brown for three years was held to own the name5 (Winchester, 1995). Outcault later secured most of the rights to his character and, through his Outcault Advertising Agency, licensed Buster Brown throughout the country (Gordon, 1998: 48-58). Since their debut in 1902, Buster Brown and his dog Tige stand as "the longest continuously licensed comic characters" still being used to sell shoes even if few parents realize the derivation of the name (Beerbohm, 1997: 5).

Almost no strip cartoonists are able to fully own their characters; an exception was Bud Fisher. By sneaking a copyright notice on a strip and registering it with the Copyright Office, Fisher was able to defend his ownership of his Mutt and Jeff strip in court. As a result, Harvey (1994: 38) states, "The soaring popularity of Mutt and Jeff made Fisher rich beyond his wildest dreams. By 1916 popular magazine articles were reporting that he earned $150,000 a year; five years later, Mutt and Jeff animated cartoons6 and merchandising, as well as the constantly growing circulation of the strip, had increased his annual income to about $250,000." Fisher's high-living lifestyle has been credited as the reason that both Al Capp7 and Ludwig Bemelmens became cartoonists (Theroux, 1999: 13-14; Collins, 1998: 120), and this reasoning for career choices continues. In the not favorable view of two "alternative" comics creators James Sturm and Art Baxter, "One cornerstone of our tradition is commerce. Comics were made to sell newspapers. The industry of comics has been grafted to the art of comics... Most publishers and cartoonists are preoccupied with creating the next 'big thing' -- hoping their characters get a TV or movie deal" (Sturm & Baxter, 1999: 97-8). An example of modern success would be Todd McFarlane. In the 1980s a journeyman penciller on DC's Infinity, Inc. and then a hit on The Incredible Hulk and Spider-Man, he left the major companies to be able to own his creations. With partners he formed Image Comics and created Spawn in 1992. He immediately formed a toy company (soon running photographs of the Chinese factory making his toys in his Spawn comic book), and eventually built a multi-media empire including movie and television versions of Spawn.8 Scott Adams' merchandising of Dilbert, while currently seemingly omnipresent, is only the latest example in a long tradition.9

As the premier licensing success of his generation, Charles Schulz has often been asked (and taken to task) about Peanuts' success. Schulz has stated:

Now the licensing thing has always been around. Percy Crosby did all sorts of licensing. Buster Brown was licensed like mad, you know. It's always been just traditional. Li'l Abner, Al Capp did a lot of licensing. But it comes upon you so slowly, you're not even realizing that it's happening. And you're young, you have a family to raise, you don't know how long this thing is going to last... And I suppose Bill Watterson came along later with his stand against licensing which is really ridiculous, but I don't know Bill, and I'm sure his life is different from mine. And he didn't have five kids to support and a lot of other things like that (Groth, 1997: 43).

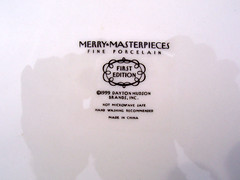

Figure 2 These two Peanuts mugs, "I think I'm allergic to morning," have the same copyright date although they were produced at least a decade apart.

An advertising campaign for Ford which used animated commercials, newspaper ads and billboards was the start, which led to the Coca-Cola-sponsored A Charlie Brown Christmas,followed by other animated specials, the musical You're a Good Man, Charlie Brown, and innumerable pieces of merchandise (Marschall & Groth, 1992: 20; Figure 2). Eventually, Schulz had enough power to say to United Features Syndicate:

'I want to own this thing. I'm tired of you selling Charlie Brown razor blades in Germany without telling me. I want to be able to do what I want to do and I don't want you doing anything but the strip. Either I get my way, or I'm going to quit.' This guy [the syndicate president], he couldn't understand at all. 'You make more money than everybody else. You've got more.' I said, 'Yeah, but I earn more. I've done more. You see, I don't want more money. I just want control so you guys don't ruin it' (Marschall & Groth, 1992: 24).

Schulz can now say, "Well, I have control over everything. My contract gives control. They can't do anything without my okay and I can do anything I want, as long as it does not destroy the property."

When asked about the growth of Peanuts merchandising, Schulz replied:

"[T]he only reason that licensing keeps getting bigger is the fact that it's simply more popular now. United Features, which never even had a licensing department before, suddenly had this enormous licensing property and we had people devoted exclusively just to looking at other companies and finding licensed properties and things, which we never did. Everything we ever did came to us, really. We never went out and sought anything. So now licensing is very big, but I'm involved with it only to the point where I want to see it done as decently as possible" (Marschall & Groth, 1992: 20).

Schulz has used his wealth to fund charitable projects. In response to Groth's question, "Can I ask you why you license the characters to corporations like Metropolitan Life Insurance? You obviously don't have to." Schulz replied, "Well, but they pay a lot of money." Groth pursued the point, saying, "But you don't need a lot of money. I mean, you already have a lot of money. Right?" Schulz asked him, "How would you like to keep this place going [gesturing at his ice skating rink] at $140,000 a month?" and laughed. As Groth continued to question the scale of Peanuts' licensing, Schulz went off the record to discuss his apparently-extensive charitable contributions10 (Groth, 1997: 42).

Schulz's positive approach to licensing (if not his charitable donations) has been emulated by other cartoonists. Cathy Guisewite has capitalized on Cathy with licenses to VISA and J.C. Penny's; the strip's shop-a-holic character is a natural link. Jim Davis' Garfield was a major 1980's hit especially with the book collections; Garfield at Large was on the New York Times bestseller list for 100 weeks, and in 1982, seven collections were on the list simultaneously. 225 million Garfield dolls with suction cups to stick on windows were sold by 1989 of which Davis said, "It was too popular. We accepted the royalty checks, but my biggest fear was overexposure. We pulled all plush dolls off the shelves for five years." Davis bought his rights to Garfield from United Media in 1994 for 15 to 25 million dollars (Johnson, 1998). Davis now publishes a 36-page, full color catalogue of Garfield merchandise and offers membership in Club Garfield for $29.95 with $5.95 shipping and handling. Garfield's success led to some cautionary notes. Berke Breathed said in 1988, "It wasn't until Jim Davis showed everyone how to overdo it that merchandising to any degree became a potential embarrassment" Spurgeon, 1998 "Viva": 10). A News of the Weird syndicated column reported that "[Gayle] Brennan and [Mike] Drysdale have 3,000 Garfield items, including 20 pairs of Garfield bedroom slippers, and plan to move to a bigger house so they can display everything" (Shepherd and Sweeny, 1998).

In contrast to Schulz's attitude stand Garry Trudeau and Bill Watterson. Trudeau's Doonesbury licensing is usually for charity. Trudeau has licensed his characters to Starbucks for literacy campaigns; permitted the Sierra Club to reproduce a Sunday strip as a poster; produced an on-line strip at Amazon.com for Reading is Fundamental; created the 1990 Doonesbury Stamp Album to benefit Literacy Volunteers of New York City; and, on Ben & Jerry's Doonesbury Sorbet, Mike Doonsebury informed buyers, "All creator royalties go to charity, so your purchase represents an orderly transfer of wealth you can feel proud of."

At Ohio State University, in 1989, Bill Watterson spoke at length on his perception of the problem of licensing:

Syndicate ownership of strips also gives them control over comic strip merchandising. Today, newspaper sales can't bring in a fraction of the money that licensing can bring. As the number of newspapers has diminished, and as the remaining papers run pretty much the same 20 strips everywhere, the growth of a syndicate now depends on dolls and greeting cards more than newspaper sales. Consequently, the quickest contracts are going to strips with licensing potential. One syndicate developed a comic strip after it had settled on the products: the strip was essentially to be an advertisement for the dolls and TV shows already planned. The syndicate developed the characters and then found someone to draw the strip. Lots of heart and integrity in that kind of strip, yes sir. Even in strips with more honorable beginnings, the syndicates are only too happy to sell out a comic strip for a quick and temporary buck, and their ownership and control allows them to do just that.

Of course, to be fair to the syndicates, most cartoonists are happy to sell out, too. Although not to the present extent, licensing has been around since the beginning of the comic strip, and many cartoonists have benefitted from the increased exposure. The character merchandise not only provides the cartoonist with additional income, but it puts his characters in new markets and has the potential to broaden the base of the strip and attract new readers. I'm not against all licensing for all strips. Under the control of a conscientious cartoonist, certain kinds of strips can be licensed tastefully and with respect to the creation. That said, I'll add that it's very rarely done that way. With the kind of money in licensing nowadays, it's not surprising many cartoonists are as eager as the syndicates for easy millions, and are willing to sacrifice the heart and soul of the strip to get it. I say it's not surprising, but it is disappointing.

Some very good strips have been cheapened by licensing. Licensed products, of course, are incapable of capturing the subtleties of the original strip, and the merchandise can alter the public perception of the strip, especially when the merchandise is aimed at a younger audience than the strip is. The deeper concerns of some strips are ignored or condensed to fit the simple gag requirements of mugs and T-shirts. In addition, no one cartoonist has the time to write and draw a daily strip and do all the work of a licensing program. Inevitably, extra assistants and business people are required, and having so many cooks in the kitchen usually encourages a blandness to suit all tastes. Strips that once had integrity and heart become simply cute as the business moguls cash in. Once a lot of money and jobs are riding on the status quo, it gets harder to push the experiments and new directions that keep a strip vital. Characters lose their believability as they start endorsing major companies and lend their faces to bedsheets and boxer shorts. The appealing innocence and sincerity of cartoon characters is corrupted when they use those qualities to peddle products. One starts to question whether characters say things because they mean it or because their sentiments sell T-shirts and greeting cards. Licensing has made some cartoonists extremely wealthy, but at a considerable loss to the precious little world they created. I don't buy the argument that licensing can go at full throttle without affecting the strip. Licensing has become a monster. Cartoonists have not been very good at recognizing it, and the syndicates don't care (Watterson, 1989).

Figure 3 Bootleg Calvin stickers and T-shirts are still widely available. These were both purchased in 1999, four years after Watterson ended his strip. The shirt reads, "Every day of my life I'm forced to add another name to the list of people who piss me off! Washington, D.C."

As one would expect, since Watterson did not permit licensing or merchandising of Calvin and Hobbes except for book collections, counterfeits flourished (Figure 3). One popular appropriation of the character was a sticker showing Calvin urinating on a NASCAR racecar driver's number. T-shirts were also a popular fraudulent item and Universal Press Syndicate won a three-quarters of a million dollars settlement against a counterfeiter in 1993 (Bernstein, 1997).

Figure 4 Dilbert, an imaginary engineer, is a natural way to advertise to real engineers. Omega Engineering provides free oversize color cards which reprint comic strips on one side and advertise engineering products on the other.

Watterson's principled stand convinced few other cartoonists, Scott Adams least of all. Adam's strip Dilbert has made him a multi-millionaire. In addition to toys, refrigerator magnets and an animated television show, Adams signed a 19-book contract for 15 million dollars (Howard, 1996). Several of the books are business management guides. The business/engineering basis of the strip has enabled Adams and United Features Syndicate to sell Dilbert in some surprising ways. The strip was licensed by Office Depot, a business supply store, while Omega Engineering put Dilbert on cards advertising equipment (Figure 4) such as the "Omegaflex Peristaltic Pump." Adams actually created a new type of licensing -- the field of corporate consulting based on comics. Lockheed Martin paid him to create Ethics Challenge, a board game for ethics training (Ginsberg, 1997). Adams is currently licensing his own character back to create a frozen burrito, the "Dilberito," and hopes to make ten million dollars in sales in 1999. In the meantime, the more than 700 licensed Dilbert products generate 200 million dollars in annual revenue for his syndicate (Steinberg, 1999).

Click here for part 2.

1. Such as Batman Collected, Adventures in Superman Collecting, Collectibly Mad and several price guides. Almost any book written on an artist, character or strip will devote some pages to merchandising. A bibliography is included after the references to help promote research which has mostly been left to collectors.

6. About 300 Mutt and Jeff animated shorts were made between 1913 and 1926.

7. Li'l Abner did make Al Capp a rich man. One of Capp's odder creations, the Shmoo, which embodied American consumerism, "became a national craze in 1949, [which] led to more than a hundred marketable Shmoo-inspired items, such as cottage cheese in Shmoo jars, Shmoo pencils, Shmoo balloons, Shmoo notebooks, and no end of Shmooiana, including Shmoo cocktails, Shmooverals, and Shmoo toys" according to Theroux (1999: 27).

9. Gordon's excellent 1998 book has a wealth of detail on licensing besides Outcault's. Beerbohm's 1997 article in the Overstreet Price Guide covers the first 35 years of comics licensing in detail. An incomplete list of major licensed strips and characters would include, from comic strips, the Yellow Kid, Buster Brown, Toonerville Trolley, Mutt and Jeff, Barney Google and Snuffy Smith, Skippy, Moon Mullins, Blondie, Bringing Up Father, Ripley's Believe It Or Not, Flash Gordon, Popeye, Little Orphan Annie, Joe Palooka, Phantom, Prince Valiant, Nancy, Li'l Abner, Red Ryder, Dick Tracy, Steve Canyon, Peanuts, Beetle Bailey, Dennis the Menace, B.C., Doonesbury, Garfield, Cathy, Bloom County, the Far Side, and Dilbert. From comic books, all of DC's characters (but especially Superman, Batman, Robin, Swamp Thing and Wonder Woman), Captain Marvel, all of Marvel's books (but especially Spider-Man, the Hulk, the Fantastic Four, and Captain America), Archie, Sabrina the teen-aged witch, Richie Rich, WildC.A.T.S., Xenozoic Tales (renamed as Cadillacs & Dinosaurs for licensing), Savage Dragon, Spawn, Teen-age Mutant Ninja Turtles, and The Tick.